Maldonado, C., et al. (2015). “Estimating species diversity and distribution in the era of Big Data: to what extent can we trust public databases?” Global Ecology and Biogeography 24(8): 973-984.

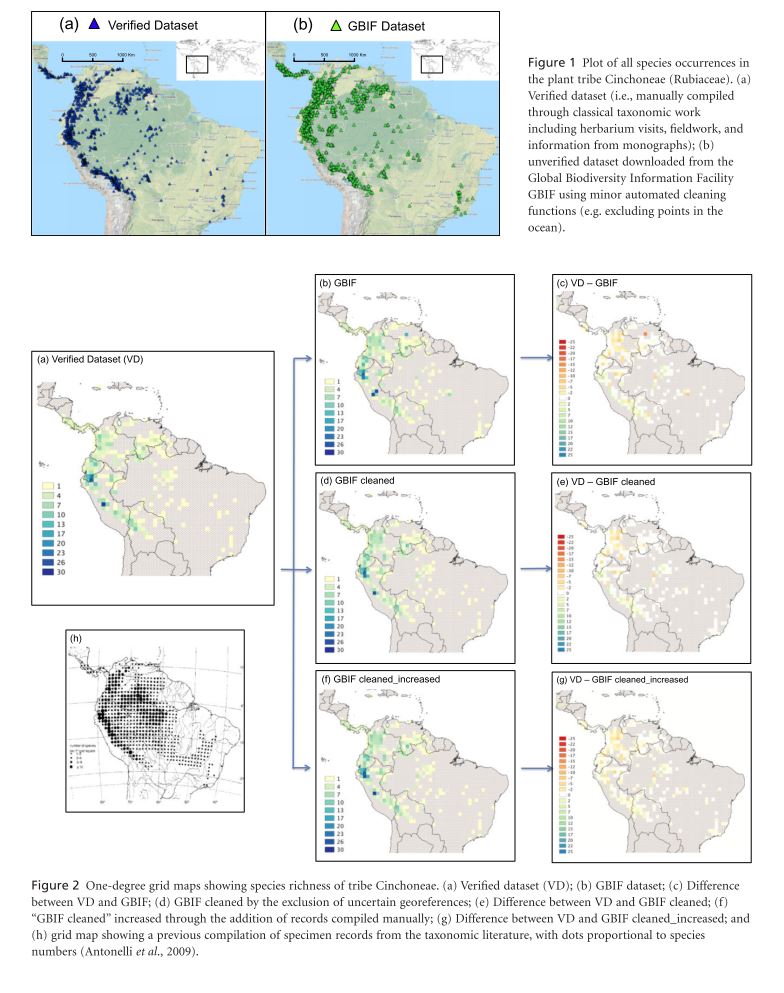

The vast records of species distributions contained in natural history collections are rapidly getting digitized and becoming widely available online. These data provide an invaluable resource for Species Distribution Modeling. One of the largest biodiversity databases is the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Despite increasing quality of data researchers should retain a critical eye for poor quality of geographic positions or erroneous taxonomic identifications. The researchers ask to what extent data in the GBIF are sufficient for prediction of distribution patterns using data for the plant tribe Cinchoneae in the Neotropics. Three data sets were taken from GBIF: (1) a non-cleaned dataset (3720 records), (2) a cleaned dataset (3572 records), (3) and a cleaned dataset with the manual addition of records from other sources (3756 records). A fourth dataset (VD) was compiled manually through classical taxonomic work using the main herbaria in South America and the Missouri Botanical Garden (2670 records). Species distribution and species richness were analyzed on all four datasets at three spatial scales using SpeciesGeoCoder. Scales are grids (one-degree cells covering the entire range of the tribe), Ecoregions (defined by WWF), Biomes (polygons also defined by WWF). Distribution and richness were also analyzed by altitude. At the grid scale the basic GBIF data identified a number of richness hotspots not identified by VD these were noted to be a result of records with country level locality data which was converted to point data using the center of the country. These erroneous hotspots were not present after data cleaning because these rough locality measures were those preferentially cleaned. At the ecoregion level, in general, ecoregions in the central areas of a number of countries had higher richness under GBIF records than VD records as a result of the poor georeferencing described above. The number of species per ecoregion was not, however, consistently higher for GBIF. At the biome level the main discrepancy is a much larger number of species in the “Tropical and Subtropical Grasslands and Savannas and Shrublands” biome under VD (34) records than GBIF (10), again a result of georeferencing errors. As above the GBIF cleaned and GBIF cleaned and increased data sets more closely approximated VD. Increasing spatial scale did not ameliorate the effect of these errors. In contrast GBIF and VD widely concur in the altitudinal ranges of species.

GBIF records have the advantage of more participating institutions and consequently more records cheaply and in a uniform format but are still plagued by taxonomic and, most notably for this analysis, georeferencing errors. Data cleaning seems to deal with some forms of georeferencing errors relatively effectively. The authors also suggest raising minimum requirements for data submission and peer-review of data in order to increase GBIF data quality before the end user.