Daly, C., Halbleib, M., Smith, J. I., Gibson, W. P., Doggett, M. K., Taylor, G. H., et al. (2008). Physiographically sensitive mapping of climatological temperature and precipitation across the conterminous United States. International Journal of Climatology, 28(15), 2031–2064. http://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1688

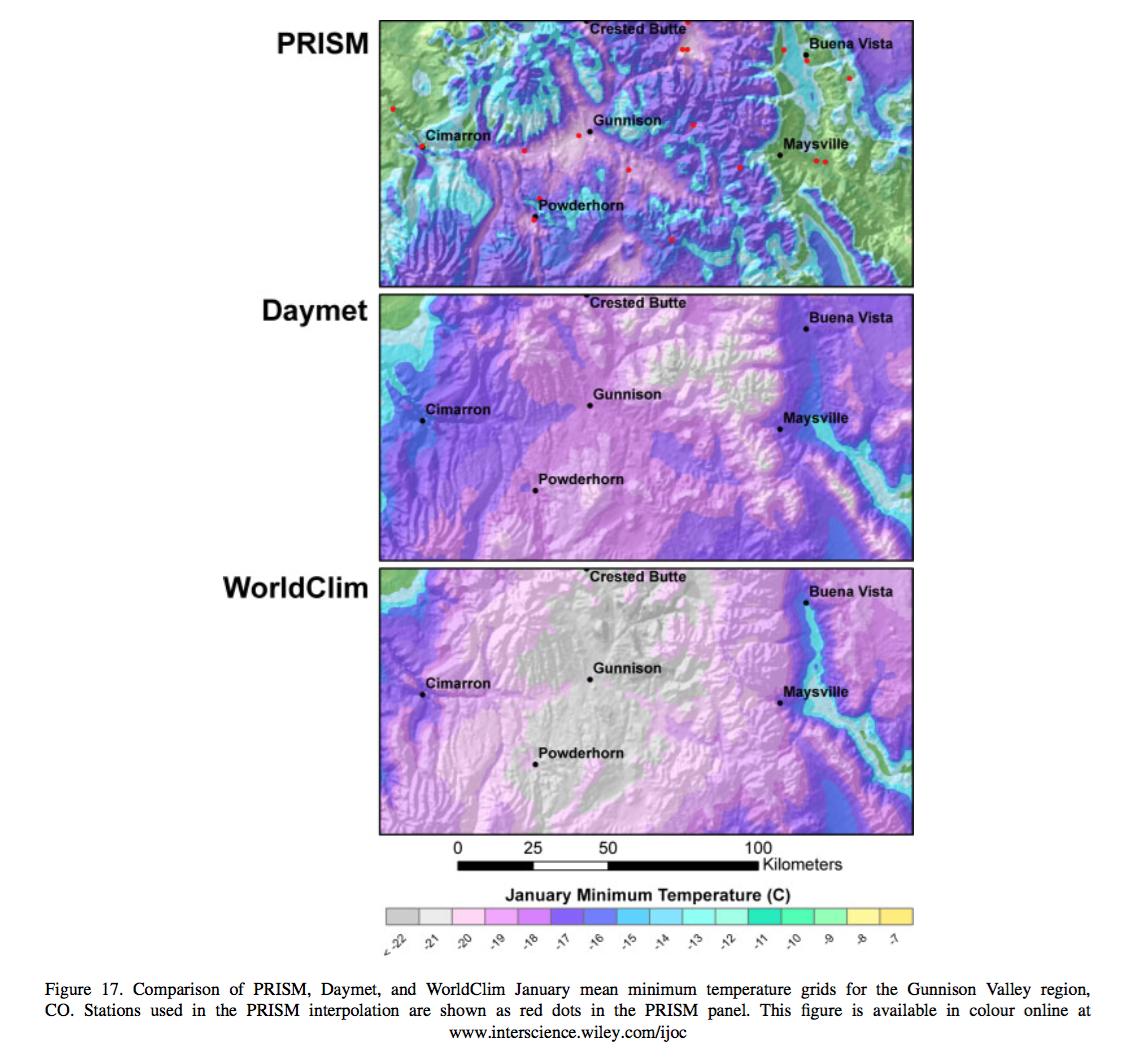

Daly et al. created a 30 arc-sec climate map of the continental United States, mapping mean monthly precipitation, and minimum and maximum temperature, referred to as the PRISM map. Similar to other models, they interpolated point weather station data from 1971-2000 over a grid using a climate-elevation regression. Station data was weighted based on nine PRISM algorithms that incorporated spatial clustering and relevant topographic data, including coastal proximity, temperature inversion potential, and location on topographic slopes. Including data such as this allowed the model to more accurately predict local climatic events such as temperature inversion in valleys and rain shadows. To clean and validate the data, local experts were brought in for each region, in addition to manual exclusion of extreme and data errors. Daly et al. used two measures of uncertainty to evaluate their model, jack-knifed cross-validation and a 70% regression prediction interval. Error was highest in the more physiographically complex areas of the US, as expected, and the two measures performed similarly with increasing area scale. When compared to Daymet and WorldClim, PRISM better predicted temperatures at high elevation, because of its inclusion of the two-layer temperature inversion, while Daymet and WorldClim had a cold bias in these areas. Additionally, the inclusion of regional coastal algorithms for the different coasts of the US led to more accurate depictions of coastal temperatures in California than the other maps. In less complex areas, such as the MidWest, however, all three maps performed similarly. The inclusion of more topographic complexity in PRISM is an improvement over similar climate grids of the US, especially in the Pacific Northwest, but offers little benefit in areas of shallow elevation gradient in the middle of the country. When available, it seems logical and worthwhile, in my opinion, to include this additional complexity, as climate is not solely dependent on elevation and does not incorporate finer scale differences.